Our First Home

From myth to meme, the idea of Hyperborea as a lost homeland for Europeans is a compelling cultural, religious, and memetic narrative

Depiction of Hyperborea by Alexander Uglanov

Origins in Classics and Art

Hyperborea is a mythical land, said to be situated in the far north. Initially written about by classical authors such as Herodotus. The land has a similar character to Atlantis in that it is a blessed, half-divine land that was set beyond the reach of normal, mortal men. The Hyperboreans were said to be fair-skinned, tall, and to live extended lives, being the favored children of Apollo.

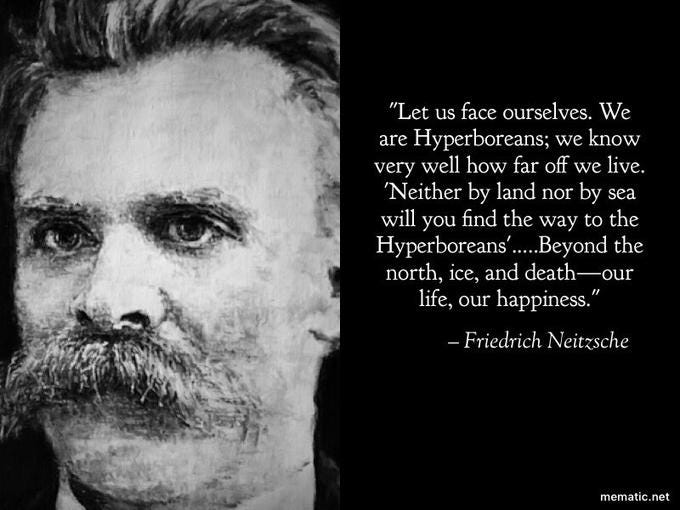

Throughout Northern European history, Hyperborea would come to represent a kind of idealized religious and cultural bastion, set beyond the reach of industrialization, Christianity, and urbanization. In much the same way medieval kings would trace their ancestry to lost Troy, so too did Hyperborea become the homeland that the northern folk hailed from, but had never seen. Nietzsche referred to the Germans as Hyperboreans in his book The Antichrist:

Even if there was no historical Hyperborea from which these cultures actually descended, the impact has been largely comparable. In much the same manner that Mediterranean Europe has long cherished and continued the artistic and cultural flame of Greco-Roman civilization, the mythic homeland Beyond the North Wind (Hyper-borea) coalesced in the northern European psyche as an idealized, heavenly representation of our own culture and folkish traditions.

Though various writers across the centuries have placed Hyperborea’s location all over the far north of Eurasia, from Scandinavia to the Tartar Steppe, nowadays the most popular placement seems to be northern Russia/Siberia, no doubt in large part due to an upsurge of interest in Slavic mythology and European identity in the dying Soviet Union, which inspired painters and storytellers like Alexander Uglanov and Oleg Korolev to create beautiful depictions of this half-Asgard, half-Eden environment.

Decline and Dormancy

Alongside other significant facets of the European volksgeist, Hyperborea would spend a long time out of the collective imagination following the Second World War. The concept of the Aryan Homeland had been adopted vigorously, and therefore colored by, the National Socialist regime in Germany. The victorious allies, capitalist and communist alike, were keen to abandon what they perceived to be air-headed and bigoted race-centered myths and move towards a very different Utopia. The ideal society no longer looked like towering wooden stave-buildings in the warm summer mountains, but like the Jetsons and Star Trek. The cultural ideal of progress, and the imagining of a materialist, secular, and technological future emerged to replace the impulse towards a mythically-inspired ideal. Ironically, for both the Soviets and the American Global Capitalists, this would fracture at the same point in the empires, a mere few decades apart.

When the Future Becomes a Dead End

During the final years of the Soviet Union, there was an upsurge in religious, cultural, and political movements that struggled against the state, and each other, to determine what the post-Soviet eastern order would look like. The concept of Hyperborea re-emerged with the force of a wrecking ball. Painters like those mentioned previously, and writers and theorists like Alexander Dugin, author of The Forth Political Theory, drawing upon the idealized ancient Slavic civilization to color their worldview. For a great many Russians watching the Soviet model being viciously parasitized by invading western consumerism, Hyperborea became a distilled, sacred Russian-ness. A cultural character that was not the Tsarist Russian imperial culture, nor the Communist worker’s utopia. Something entirely distinct, and yet recognizably their own.

The capitalist West is finding itself presently in the same predicament. The vision of the American Dream has soured into a punchline. The economy, the golden calf which justified every ill action domestic and foreign, is currently committing suicide. Being a country comprised of immigrants and expatriates from all corners of the world, the United States has become like a mix that failed to gel, and has instead found itself a messy, clumped and viscous slop. The future of the Jetsons and Star Trek is never coming, and in hindsight only demonstrates the deep naivete of the previous generations.

The youth of the West have been left without a culture to protect, or even participate in. Indistinguishable roads lined with the same gaggle of megacorporate shopping centers, with pandemic masks and wrappers lining the sides of the road stained brown by engine exhaust. A great many, frustrated by the incongruence between what they were brought up to believe (tolerance, diversity, equity, fairness,) and what they have found the world to be like, have resigned themselves to blindly ripping down everything. But even these spurned idealists are lost in the futureless haze of modernity, they have only the most vague and emotional assertions about the world they actually want to live in. Having been convinced by corrupt educators about Marxist historicity (which we today call progress, as in, human life is naturally going to arrive at perfect communism, if it weren’t for all those capitalists/racists/misogynists/white people et cetera ad infinium.) These bitter youth know they’ve been robbed, but they lack the capacity to even envision what it is they have lost.

But, in mirror to the fall of the Soviet Union, there is a growing segment of the youth who have also taken to Hyperborea. Thanks in large part to the rise of social media, Hyperborea has swelled from merely a cultural holdout of Russian-ness, to an idyllic depiction of a prechristian, Solar European culture.

Going Home

Hyperborea in the modern Solar sphere, and in my own work particularly, is an expression of the entirely embodied, realized lifestyle of Solar spirituality. Deeply connected to nature and myth, raising temples and ornate halls in the deep wilderness, beautiful women in traditional dress dancing around the maypole, warriors participating in rites of honor amidst standing stones alongside wonderous technology and magic alike.

The First Home, Urheim is anti-future, the idea that we cannot and shouldn’t try to shed our traditions and spirituality, as that is what makes us human. Ironically, fantastical mythology is grounding, as it keeps our most fantastical imaginations grounded in where we came from, and what is important to us. We are living now through the death of progress, the idea that in shedding ourselves we can find something more pure.

When artists, trainers, writers, builders, craftsmen, and fighters in the solar sphere online tag their location as “Hyperborea,” they are contextualizing their achievements and efforts as part of a journey towards that mythic place. To journey out of the ruins of this inhuman culture of blind, idiot capitalism that overdoses itself to death, towards something our ancestors would recognize and be proud of.

As a commenter on one of my posts so eloquently described: “A return to the Golden Age isn’t a time or a place, it’s a mindset. A set of ideals and values. The Golden Age is timeless within our hearts.”

What activists and world leaders get wrong is that Utopia isn’t meant to be reached, like all ideals it sits as a North Star, the single anchored point in men’s souls that guides them towards something greater. A well-lived life is a pilgrimage home to Hyperborea, and we will not truly reach it until we draw our last breath.